Keywords: medieval urban self-government politics political thought values

attitudes doctrine authority community sovereignty law hierarchy justice

election decision-making consent consultation representation council mayor

political conflict maladministration folkmoot processions guildhall riot

Political theory

Relatively few

medieval

philosophers focused their attention on political aspects of

human activity. For most, power structures and the task of government

were an integral part of a larger picture of the relationships between

Man and Nature and between Man and God. It was not until the

Late Middle Ages that we begin to see the notion emerging that

political science might be something worthy of study in its own right,

and then it was less from an abstract perspective than from observing

actual practice and trying to rationalize this within existing theory

and norms.

That being the case, we can hardly expect to find explicit statements

of political doctrine issuing from pragmatic townsmen, few of whom had

much formal education. For the most part, we have to infer their

political views and values from the way they acted, the institutions

and procedures they put in place, and the way they expressed themselves

in documents related to the operation of government – documents

such as charters of liberties, borough custumals and the by-laws

that succeeded them, and records of legal disputes. Even here we are

treading on uncertain ground, for most of the documents that have come

down to us are official records, undetailed, formulaic, and impersonal;

we cannot be sure whether (or to what extent) they reflect the

political attitudes of the general populace or superimpose the

terminology and perspectives of the clerics and lawyers who drafted

them. Historians tend to rely on political crises to bring forth

something more than the routine expressions of political viewpoints,

but here again it is hard to know whether what was said in the heat

of conflict represents everyday opinion. Nor should we automatically

assume that principles, whether explicit or implicit, were necessarily

upheld in practice.

Uneducated townsmen may have been, but stupid they were not. It would

be a mistake to assume that they acted solely out of self-interest,

or were driven purely by some kind of social and/or economic determinism,

in developing their political institutions and behaviours. They did

not operate in an ethical vacuum or independent of the larger

political context of lordship. The Church promoted values such as

peace and justice which had political dimensions, and the State (itself

a relatively modern concept with limited applicability to the

medieval period) had structures for formulation of law and the

administration of justice that embedded political values. While

we cannot be certain that the laymen to whom these were preached or

on whom they were imposed shared these values, it is unlikely they

were unaffected by them.

Nonetheless, the concepts historians have liked to use as yardsticks

to characterize urban government – notably democracy and

oligarchy – were not

available for most of the Middle Ages, and even when they became so

were largely the preserve of philosophers. In applying such concepts

retrospectively we inevitably risk a present-minded interpretation of

the past. However, although many values were shared, there was not

a uniformity in political outlook within medieval urban society.

Those medieval thinkers who wrote on, or around, politics reveal a

range of ideas so that it would be hard to point to a political orthodoxy;

we can expect a corresponding diversity of ideas, if less developed and

less articulated, to have existed among the masses.

During the High Middle Ages philosophers naturally focused on

autocratic systems and on issues such as authority and sovereignty,

as a medieval world emerged in which popes, emperors and kings were

key players. It was necessary to define the relationship within

Christendom between these players, and the relationship of each with

their subjects. But the twelfth century, in particular, saw the rise

of urban communities with some measure of political autonomy (the

degree varying from place to place within Europe) and with increasingly

complex societies and internal power relationships. One of the more

prominent of the traditional conceptualizations of medieval society,

differentiating three orders – those who fought, those who worked,

and those who prayed – was as early as ca.1100 being seen by some

as needing modification, through addition of a fourth order: townspeople.

But even within that fourth order there was not homogeneity. The growth

of long-distance trade and the harnessing of rural and urban resources

to fuel such trade, population growth prompting increased immigration

into towns, and the integration of towns into the administrative

framework of larger territorial entities, all helped bring about

increasing specialization of labour: traders, producers, administrators,

professionals. This accentuated stratification within urban society

meant that such a society would encompass a range of goals and interests

that had to be channelled, resourced, and harmonized through politics.

At the same time that such developments were underway in secular society,

organizational diversity was becoming more marked within the Church,

notably with the formation of new religious orders of a fraternal

character.

These developments must have helped prepare the ground somewhat for

receptivity to Aristotelian ideas, when they were rediscovered by

scholars and made available in Latin around the mid-thirteenth century.

To Aristotle, of course, the city was a natural political unit and (in

the absence of a strong religious philosophy that had a single divinity

delegating power to earthly representatives) it was easy to view

the community as a source of authority, and democracy as one of

several viable political options. Aristotle himself preferred timocracy,

a benevolent rule by the most honorable members of society (the term

was corrupted by medieval thinkers to be more akin to oligarchy, but

aristocracy expresses a similar concept to the original use of timocracy).

Aristotle's concepts helped medieval philosophers come to terms with

emerging urban powers. Above all, attentions were focused on

the city-states of northern Italy, closest in essence to those of

ancient Greece; the Italian cities' efforts to assert freedom to

the point of autonomy from any external authority made it necessary

to produce some kind of rationalization, and some of the greatest

political philosophers of the Late Middle Ages came out of that milieu.

Unfortunately for us, towns in England, or elswhere north of the Alps,

received far less attention; the other side of that coin is that

the work of political scientists was less likely to have any influence

on the attitudes of English townspeople.

We should not think that Aristotelianism was the catalyst for a

revolution in political thought. There was a long-standing foundation

for the notion of the people as a source of authority, in the

popular assemblies that made decisions affecting rural communities

and in custom – practice given the force of law through

repeated observance by a community – governing local communities.

Concepts from Roman law – not least the famous maxim from

Justinian that what touches all must be approved by all – also

prepared the ground for Aristotelian ideas, while a growing appreciation

of Ciceronian civic doctrine likewise bolstered the efforts of those

integrating cities into the medieval political framework. But

perhaps above all we must recognize that Christian ethics and values

remained throughout the Middle Ages the foundation stone for all

philosophy, political included. It was not Aristotle's convictions

but more his concepts and language that were adopted and adapted

for integration into established Christian thought.

This was a gradual process.

Thomas Aquinas

made the first major effort in the late thirteenth century; in so doing,

he did much to make Aristotelianism more palatable to Christian thinkers.

He took the descending theory that was inherent in Catholic orthodoxy,

in which power was delegated from God, through the Pope, to princes,

etc., and fused to it Aristotle's view of Nature and natural law as

a source of human civilization and laws; this meant that secular

government could claim to obtain its authority from God via the agency

of Nature, without the intermediation of the Church. From this viewpoint,

an ascending theory was possible and, without seeking to undermine

the hierarchical establishment (although his ideas provided the fuel

for later anti-hierocrats), Thomas acknowledged the existence of

democracy in the sense of power emanating from the community:

"they may elect their leaders from the people, and the election of

leaders belongs to the people"

[Summa

Theologiae, I-ii, question 105, article 1]. It followed from this

that the rulers represented the people (unless one wished to adopt

the extreme view, not unknown in the Middle Ages, that election

irrevocably transfers power to those elected). Although Thomas did

not employ his arguments in an anti-monarchical fashion, he did follow

Aristotle in concluding that the optimal form of government was a kind

of limited monarchy, in which there was a dominant ruler at the head

of a state but that ruler governed with the assistance and advice of

the best men of the state, and through consultation with the people.

What Aquinas had started, successors extended to the logical conclusion

of portraying the feasibility of sovereignty of the people. Thinkers

such as

John of Paris,

and Marsilius of Padua

moved towards the conclusion that any ruler – unless behaving

tyranically – required the consensus, or at very least

the acquiescence, of the people to exercise their authority. In essence,

that authority therefore derived from the people; and what the people

could give, the people could take away.

Bartolus of Sassoferrato

and his student

Baldus of Ubaldis

came at the subject from a different perspective – that of

legal realists observing what was going on within the

Italian city-states – but arrived at essentially the same

conclusion: that the will of the people was source of authority for law,

simply because their consent to be subject to the law was the basis for

its effectiveness. Observing that customary (unwritten) law was founded

on the tacit consent of the community, Bartolus argued that the explicit

consent of the people could equally well give rise to new, written laws;

thereby, since government was viewed essentially as the formulation,

application, and enforcement of laws, a people could be self-governing

within its own territory.

There was thus a dichotomy, or perhaps ambiguity would be a kinder

description, in the political system of medieval Europe. Descending

and ascending theories of authority co-existed necessarily. Even

though autocracy was the most conspicuous form of government, fostered

by the requirement for wide-territory authority maintained partly by

military might, by the inheritance of imperial ambitions, and by

the theocratic underpinnings of the Church, there was a strong tradition

of collective decision-making through institutions such as the folkmoot

or Church councils. Monarchs were not in a position to be

absolute rulers; their coercive powers were limited. For their

orders to be carried out, they relied greatly on co-operation from

local authorities. Consulting with selected subjects and obtaining

their consent to important acts (e.g. legislation) was a practical

necessity, perhaps especially in England where the feudal character

of kingship made it particularly dependent on support from at least

the king's immediate (baronial) subjects. England's towns, although

not in a position to aspire to the communal autonomy of some of

their continental counterparts, nonetheless held some

power – particularly economic – in the kingdom and

the king ignored them at his peril. It was in his best interest to

allow them a measure of self-government. That self-government itself

reflected a political dichotomy, in which principle and practice did

not always walk hand-in-hand. Even though democracy and oligarchy

as such were foreign concepts to the medieval townspeople, we can see

expressions of each, both in the values and in the practice of politics,

sitting – sometimes comfortably, sometimes less so – side

by side in the towns.

|

The portrayal by Bristol town clerk Robert Ricart of his home town

reflects social and political perspectives that he shared with other

members of urban patriciates.

(click on the image for an enlarged version and more

information)

|

Political values and attitudes

What then are some of the values and attitudes that shaped

political beliefs in English towns? One of the most commonly encountered

terms with political implications is that of "community". Before

exploring what this meant, we must first rid ourselves of any

associations with egalitarianism or libertarianism, two fundamental

tenets of modern democracy. The perception that medieval society

was naturally divided into orders or ranks, just as modern society

is seen as class-based, was so deeply ingrained that it was little

discussed and rarely challenged. The Church blessed this belief by

emphasizing that all orders had an important role in contributing

to the well-being of the whole; the reward for the common people

being content with their lot was the levelling that would take place

in the afterlife. Aristotelian ideas did not alter this, for

he had acknowledged that the challenge of government was to balance

the often conflicting interests of poor, rich and middle class through

a system that was politically stable.

Within urban society there had probably always been a reasonably

clear socio-economic differentiation and the gap between haves and

have-nots became more pronounced as the economy sophisticated.

Successful entrepreneurs became quite rich and invested in land purchases,

partly through aspirations to rise into the ranks of the gentry and

partly because those lands generated raw materials that fuelled their

commerce. Meanwhile, the urban population was swelled by individuals

or families lacking sufficient land for self-support, but most of

these only joined the ranks of wage-labourers or the impoverished.

In the middle – for the general perception was, as in Aristotle's

day, that of three urban ranks – established craftsmen or small

retailers tried to protect themselves from new competition, or uphold

their interests against those of the mercantile element, by creating

associations (which we today refer to, not strictly accurately, as

gilds) that controlled access to and regulated the performance of

skilled occupations. While there were no rigid barriers to

social mobility, only a minority were able to make a success of

themselves; for the remainder there must have been frustration or

hopelessness, buried under a facade of acceptance but occasionally

prepared to boil over into violence.

Where there was hierarchy there were relatively clear authority structures;

everyone knew his or her place, even if that place need not be considered

fixed. Hierarchy was therefore considered conducive to order (the

just accommodation of social needs in a directed, non-violent fashion),

and in the interests of order the Church was happy to sanctify

secular authority. In most places, and certainly in England,

hierarchical authority was accepted as natural. Rights were not seen

as inherent to the human condition, but particular to an individual or

group, acquired through specific and documentable grants from an

authority or through established practice from time immemorial

(although in the Middle Ages, time beyond memory sometimes meant

only a generation or two). Liberty was not an idealistic, generalized

principle but a pragmatic goal involving the acquisition of

immunity from external authority in specific areas of jurisdiction.

Charters of borough liberties were thus

instruments for according rights and transferring jurisdiction, with

the concomitant authority, to the towns. In those towns liberties were

mainly accorded to organized groups; affiliation with such groups

enabled individuals to share in the liberties. One such group was

the community.

"Community" was therefore a term with political connotations; but

like many medieval terms, it seems to have been used imprecisely, or

with the meaning varying from one occasion to another. Sometimes

applied to the urban populace at large, more often it appears to have

been intended to convey those residents who had some share in the

special advantages and obligations of a self-governing town, and in

whose interest and for whose benefit local government acted. There

followed from this its applicability to public meetings for the

purpose of learning of, or giving input on, governmental decisions.

Initially at least it was used to encompass both ruled and rulers.

Only towards the close of the Middle Ages, when constitutional

developments had led to the establishment of political estates within

the larger towns, was it used in ways suggesting intentional

differentation of those two groups. Be that as it may, when

the townspeople of Ipswich gathered in June 1200 to set up institutions

for local self-government, what they were doing in essence was to

create a political community: a consociation whose constituents

agree to exercise their rights in an ordered fashion for mutual benefit;

it may be significant that the term "community" in fact does not

begin to be used in the record of proceedings until the key institutions

were in place and empowered to act on behalf of the burgesses.

It is sometimes said that a key characteristic of medieval society

is that it was organized into collectives, whether formal or informal,

and that for most individuals identity came only through membership

in such groups. There is some truth in this, but it is a generalization.

The tithing system is

one illustration of the importance of belonging to a group. Guilds

and parishes are other examples of such collectives, or greater or

lesser degrees of organization. There was no medieval concept of,

or term for, "the individual"; legal texts instead used vaguer terms

that meant "someone". And we may note that persons of the same name

were differentiated by assigning them (or them taking) surnames that

in most cases associated them with a larger group – whether

family, occupation, or territorial unit. However, it would be wrong

to think that medieval people had no sense of individualism;

economic entrepreneurialism, along with preparedness to violate

communal norms, provide indications that self-interest was a very

real driving force. Nor should we forget that, for all its support

of social structure, the Church's preoccupation was with the salvation

of souls on an individual basis.

The purpose of a community was to give strength and support

to individual needs and aspirations, on the assumption that such

needs and aspirations were shared by members of the community, and

to protect individual rights or the liberties with which the community

had been endowed. It was the creation of unity (of overall purpose)

out of diversity. To achieve this, it follows that any community

needed and wished to organize and govern itself. At the extreme end

of the concept, the "commune" was an association whose goal was

to achieve independence from external authority, by force if necessary,

through presenting a common front of persons bound to each other by

an oath of mutual support. Often associated with revolutionary movements,

the "commune" was more a continental phenomenon, only very occasionally

manifesting itself in English towns; although its spectre was often

raised by parties to political disturbances, charging their opponents

of making "sworn confederacies". In fact the whole concept of

citizenship, which required the taking of an oath of allegiance

(e.g. Lynn,

Ipswich), was not so very far

from the communal principle. But for the most part a community was

a far less revolutionary association that philosophers such as

Aquinas portrayed as a desirable within society, arising from

the natural human need for sociability.

If a community was an association of persons with common interests

and mutual obligations, then it also followed that a "common good"

could be identified. This is another concept that reflected

political values of medieval townspeople; the notion is often

captured in phrases talking about something being done for the benefit

of the community. Individual interests were subordinated to

communal interests, and private possessions could be called upon

to meet communal needs (e.g. taxation). Lesser associations, such

as craft gilds, might be regulated or even suppressed by government

so that the interests of their members did not override those of

the community at large. Just what the common good might be at any

given point was, of course, open to interpretation; the concept

of community might be invoked by either side in a political conflict,

with those challenging the establishment using the term to infer

a solidarity amongst an aggrieved populace, while those defending

used it to suggest a state of orderly social relations they were

trying to protect. Despite its susceptibility to interpretation,

"community" was clearly intended to refer to an association imbued

with some measure of political authority and capable of delegating

that authority in order to administer itself. In that respect,

charters granting incorporation

towards the close of the Middle Ages did little more than formalize

a situation long existing in the towns.

If day-to-day administration was in the hands of the upper crust of

urban society, this was not inherently alarming to the rest of

the community. Political authority was considered to be founded upon

the law, and one of the principal tasks of government was to uphold

the law. As noted above, early law (in the form of custom) had its

origin in the will of the community. Those who governed were just

as much subject to the law as anyone else, and faith was put in

the supremacy of law – or more accurately of justice, the upholding

of rights (ius). While absolute social equality may not

have been a value to which townsmen subscribed – even though

some custom emphasized

equal opportunity – equality before the law was. It was

believed all, poor or rich, should receive a fair trial – that

is, procedural justice – without favouritism being shown by

judges to any party, however powerful. This is evident from stipulations

in officials' oaths or custumals (e.g. see the several mentions of

this in the setting up of

self-government at Ipswich), as well as in complaints of

judicial maladministration in the context of urban political conflict.

The same concern with equal justice was seen in the attitude towards

taxation, that it should be fairly assessed; this too was a

recurring source of complaints against borough governments. Such

complaints suggest that the practice of government too often did

not match the ideal.

Nonetheless the ideal of rule by law was there, if perhaps less

ingrained than it is today, and adherence to the principles underlying

the concept of community and common good was expected to assure that.

The common good had two dimensions: on the one hand, the pursuit of

what was beneficial to the community in terms of meeting the

material needs of members; on the other, the fostering of moral virtue.

The purpose of law was to encourage moral behaviour. The view of

government as a "stewardship of the rich" was based on the assumption

that the wealthier members of society were worthier – that is

better qualified (in part from an ethical standpoint) –

to administer justice and act for the common good. Such men had

a major stake in the material well-being of their community; success

in life had brought them wisdom and experience in managing affairs;

they had a natural authority, which came from the respect they

had already earned within the community; and as men already wealthy,

they could afford the time required to serve their community with

minimal financial reward, and they should be capable of generosity

and less susceptible to corruption. Wisdom and virtue were

the qualities that it was hoped the urban upper class would bring

to the administration of existing law and the formulation of new laws.

Such appears to have been the theory; although to find it

explicitly expounded we have to look outside England, to writers

such as Brunetto Latini, we occasionally catch sight of these

principles in borough documents such as officials' oaths of offices

(e.g. the mayoral oath at

Bristol).

Power and wealth thus went hand-in-hand with the acquiescence of

the community. Since all English rulers, from kings down to bailiffs,

were considered to be limited in the exercise of power by custom,

law and the need to consult with the community, what was of concern

was not whether government was democratic or aristocratic, but whether

it was just and beneficial. An important part of the task of a

just and beneficial government was to achieve and preserve peace,

love and harmony across the social hierarchy which, as noted, was

not itself open to question; such was the glue that held a community

together.

Justice was not simply a matter of legal administration, there was

also the question of social justice. It was the duty of government

to protect the defenceless and provide for the needy; hence the

courts showed particular concern for the rights of widows and orphans,

and urban governments involved themselves in the administration and

even the founding of hospitals for

the sick and the impoverished. Interestingly, this may have benefitted

the ruling class most, as there was a distinction between

the poor worthy of charity – those downwardly mobile, having

suffered from misfortune – and those unworthy, having fallen

into poverty through sin or laziness. For the wider community,

benevolent rule manifested itself in the provision of public facilities

such as a supervised marketplace, sanitation measures, a water supply,

the maintenance of roads and bridges, and police and defensive

provisions. Insofar as medieval urban society was fraternalistic,

it was so in the context of benevolence within a stratified society,

rather than an egalitarian sense.

Not only charity, but the promotion of amicable relations was a

moral duty of government; which is part of the reason why government

was prepared to intervene in personal disputes to try to mediate

a peaceful resolution. In a similar fashion, maintenance of

peace and order (which, we must remember, was at least as much in

the interest of government as in that of the governed) required that

dissent not be tolerated to the point where it brought about a

disruption of social or political relations. The late fourteenth

and fifteenth centuries saw many urban governments specifying acceptable

and unacceptable behaviours at council or community meetings.

If we can see that justice, benevolence and social harmony were

yardsticks according to which the quality of government was measured,

it is not so easy to see how such ideas came to be infused

as fundamental urban political values. It is hard to imagine that

townsmen were avid readers (or rather, in most cases, the audiences

of readers) of the treatises of philosophers and theoreticians such

as those mentioned above. To some, perhaps a large, extent the way

in which government was fashioned was dictated by a limited set of

options available as solutions to problems common to most societies.

The options were narrowed and defined by the context of Christianity

and its moral and ethical teachings, by the emerging model of

national government and the influence of that government over

the developmental course of local administration, and by a long-standing

tradition of communal decision-making and informal law-making.

On the other hand, we cannot entirely rule out either direct or

indirect influence of some of the ideas of classical or

medieval philosophers. The presence of an adapted version of

Latini's tract on good government among London records, although

an isolated occurrence, shows that some townsmen had enquiring minds

and might see the relevance of such ideas to their own environment.

This was London, of course, a law unto itself among English towns;

but by the same token a source of influence and inspiration. We should

remember that not all townsmen were uneducated. Clerks, notaries,

lawyers became increasingly common participants in urban government

during the Late Middle Ages; some are visible among reform movements

that challenged the political status quo in towns, and perhaps they

may been channels for populist political ideas, however diluted.

The clergy itself could be influential among the townspeople to whom

they preached; the level of education among the clergy varied, but

ideas spread through the universities might well have filtered down

to townsmen. A diversity of political viewpoints existed within

the ranks of the Church; friars in particular could be relatively

radical, although we should avoid reading anything sinister into

the occasional use of friaries for meetings of political dissenters,

while the fact that clergymen are sometimes listed among groups

making political mayhem may also not be significant in regard to

the introduction of populist ideas.

Another mechanism for the spread of ideas or news of

political developments was travel, both by traders and pilgrims.

In the case of towns that were destinations of international commerce,

residents were well-positioned to learn from foreign counterparts

what was going on in the communes of France or the city-states of Italy,

for example. But even the smaller towns had a measure of access to

these types of travellers. Nor should we ignore the filtering of

political ideas through London. However, in the final resort it

is probably sufficient to think that the ideas expressed by men

like Latini (who was less concerned with the type of government,

he incorporating concepts associable with both descending and

ascending theories, than with its quality), Aquinas, or even Bartolus,

were themselves shaped not only by classical forbears but by what

was to them a rational interpretation of the nature of society and

its political dimension; and that the same ideas might occur to

others who were also, for their own reasons, preoccupied with issues

of governance.

|

Political values at opposite ends of the spectrum are reflected in

public gatherings for folkmoot meetings (perhaps not dissimilar from

the gathering above) and civic processions (below).

(click on the images for enlarged versions and more

information)

|

|

Consent and representation

If both philosophy and tradition provided grounds for an

ascending theory of authority that stood in juxtaposition to

the autocratic rule that, on the surface, seems more characteristic

of the Middle Ages, there remains the question of how and to what

extent the principle of the community as the source of authority

was manifested in practice. The dichotomy between theory and practice

has often led historians to dismiss the former as empty and characterize

English urban governments as oligarchies. However, the seeming

contradictions are perhaps of the essence of politics. That

the majority of even the enfranchised male adult residents of

a town had little say in the day-to-day decision-making of

local government is no less true of modern democracies than it was

of the medieval situation, and does not diminish a principle that

is today considered in essence democratic. The idea that

decision-making (that is, legislative) authority was grounded in

the people was, if not a universal, then a widespread opinion for

much of the Middle Ages; from this viewpoint, the role of

the executive was to uphold laws authorized by the community. We

may note that it was not a usual feature of borough charters to

include grants of the right to make by-laws, probably because it

was taken for granted – although the charters, by prescribing

the scope of borough jurisdiction, defined the limits within which

local legislation was valid; occasionally the explicit recognition

of the town's lord was sought for such a right, but perhaps only in

special circumstances dictated by particular need.

A concomitant of the people-as-source-of-authority principle was

that executive officers were servants of the community, appointed

by the latter to operationalize its will, expressed in a way that

might better be thought of as collectively than democratically.

The situation in England was of course complicated by the fact that

towns, although self-governing in some respects, were also under

the authority of the king; so they were subject not only to laws

made locally but those imposed from above, and their executive was

answerable to both community and king – the issue then became

one of prioritization, and in that battle the growth of a national system

of administration gradually won the upper hand. But we should not

let this situation muddle us. The election of representatives to

whom popular authority was delegated was a well-established principle

in the medieval period, in both the secular and ecclesiastical spheres,

at times applying to rulers at the highest levels of power. In fact,

there was a large literature discussing elections in the

ecclesiastical context and the way they transferred authority.

Documents from urban archives are by contrast far more focused

on procedures than principles, but it seems clear that elections

were political events in which at least the entire

enfranchised citizenry, if not the (male adult) community-at-large,

was expected to participate, and lip-service was generally paid to

the idea that officials were elected by the community, even when

the actual practice was somewhat different.

For power – which requires both means and opportunity – inevitably

rested on consensual at least as much as coercive foundations. This

is well illustrated by events at Ipswich in 1344 [see conflict_ipsw1.doc],

where the bailiffs felt powerless to apprehend the assassins of

a prominent but unpopular townsman because the community condoned

the deed and not even a handful would not support the bailiffs in

the execution of their duty. It has already been noted that

the English monarchy itself was reliant on consensual support from

the baronial community which – as John, Henry III and Edward II

discovered – was willing to resort to rebellion to restrain

the king from absolutist tendencies and ensure that the nobility

was properly consulted, and their advice listened to, on matters of

national import requiring decisions. The barons even recognized that,

in a sense, they were only representing the community of the realm;

those who overthrew Edward II and Richard II made some effort to

evidence popular consent for their actions. A powerful group of

barons in 1258 used force to impose on the monarchy constitutional

and administrative changes (the Provisions of Oxford, expanded

the following year as the Provisions of Westminster), which among

other things established a new consultative council that advised

the king on matters of state, required the broader community to be

consulted through parliaments held three times a year, controlled

appointments to the major bureaucratic posts, and reformed abuses

such as excessive taxation. The same sorts of concerns are seen

in movements for governmental reform at the local level.

Taxation, which necessitated the infringement of the rights of

the king's subjects, and legislation were in particular matters

felt to require community consultation and consent, and parliament

came to be the principal mechanism through which this was achieved;

it was a kind of court that came to assume a conciliar role. While

parliament's emergence as a regular tool of government served a number

of differing ends, including the monarchy's efforts at centralizing

administration, and we should beware of thinking of the

medieval institution as a fundamental of democracy, it did represent

for the nobility a venue through which they would be consulted and

could give or withhold their support for royal initiatives, and

for the common people a public forum in which their concerns and

grievances could be put before the king. The king was not,

constitutionally, obliged to pay attention to his barons or

his commons, but he was expected to act for the common good; from

a practical standpoint he required their willing assistance to

govern effectively. Edward I paid explicit homage to the

political principle that decisions affecting the community must

be agreed to by that community.

At the local level too, taxation and legislation were types of

governmental decisions felt to require community consent; it is

hard to say to what extent this mirrored and to what extent it

paralleled developments at the national level. Historians are not

certain what are the practical implications of phrases such as "by

the consent of the community", before the fifteenth century when we

see the spread of lower councils intended to represent the community

and give consent on its behalf. But the very fact that, prior to

the introduction of those mechanisms, such phrases are almost

ubiquitous in urban records of important decisions taken by the

borough authorities is itself a clear indication of the perceived source

of authority. Although some historians continue to argue that

"urban political theory normally expressed a descending concept of

political power" [Rigby and Ewan, Cambridge Urban History of

Britain, 305], on the grounds that jurisdiction was accorded

to executive officers by the king or other lord of the borough, this

is not the view expressed in most medieval urban records.

To dismiss phrases referring to community consent as rhetoric,

lip-service or mere formulae simply because they are ever-present, or

to assume that consent simply masked acquiescence in decisions made

by an elite, is to miss the point. The rare occasions when we hear

of the community rejecting proposals are suggestive that consultation

may well have actually taken place, as opposed to being taken for

granted, even though that consultation may have been of a yea-or-nay

character, as opposed to meaningful discussion. In most cases,

rejected proposals likely never saw the light of day in urban records.

At the same time, nor should we be naive enough to imagine that

the community at any time took the lead in governmental decision-making,

or that political assemblies were necessarily attended by

the entire qualified populace, or even a majority. Today

political apathy contributes to giving the community a largely

acquiescent role in most political decision-making, and we should

not expect higher standards from our medieval forebears. Given

the belief, noted above, that government was best conducted by

those of moral fibre and prudent judgement – the

probi homines or

prudhommes – it is most probable that the community

was content to approve much of what was put before them, something

that does not diminish the importance of that approval. And there

is ample evidence that items of business of genuine concern to

the community would draw large crowds to the town hall to hear

debates and express opinions; this in itself posed a problem for

government.

Consultation involved tapping into the collective wisdom of

the community (a notion that increasingly fell into disrepute as

the growing socio-economic divide fostered contempt for the rabble).

Decisions that could be described as consensual were more likely to

win adherence from the populace, and provided legitimacy for

the suppression of any future opposition or resistance. There was

a low tolerance for dissonance in society, for fear that dissenting

opinions might lead to factionalism or violence; in the absence of

strong policing mechanisms, there had to be reliance on

consensual behaviour, or at least the appearance of consensus.

Urban governments preferred to have it recorded that decisions

were reached or elections made through unanimous agreements, and

criticisms of government or any of its members were increasingly

addressed through by-laws that imposed fines or, where the dissenter

was unrepentant, sterner judgements to the point of exile. In

the same way, higher levels of government were often reluctant in

intervene in local disputes (unless a sustained breakdown of

public order occurred), preferring for matters to reach an accord

locally.

The impracticality of the community as an institution of government,

even if its role were restricted to consultation and consent, must

have been as apparent to our medieval counterparts as it is to

the citizens of modern democracies. Just as authority to administer

had to be delegated to executive officers, so the authority to

deliberate and make decisions had to be delegated to a select number

of representatives. In most if not all cases this had probably come

about naturally before any constitutional provision was put down

in writing. Again, it made sense in the context of medieval values

for these representatives to be drawn from the prudhommes,

the wiser men of the community, and the domination of town councils

by such men should not fool us into thinking of urban government as

oligarchic. Towards the close of the Middle Ages the need to obtain

the best advice manifested itself in the retention of legal experts

by those towns with a budget that could accommodate the expense.

Even when chosen from electoral districts (which we do not know

to have been general practice) councillors were intended to be

representatives in the sense of acting for the entire collective,

rather than particular neighbourhoods or interests within

the community.

Consilium is another of those imprecise medieval terms;

it is often difficult to tell from the context whether it refers

to a relatively informal process of obtaining counsel, or suggests

a more formal institution, the council. Although a council was

apparently a formal component of the constitutional arrangements

established when Ipswich acquired

rights of self-government in 1200, we cannot be sure that this

unique account is either reliable or typical; although, if we can

put our faith in it, then it would seem that a council was no

innovation in English communities in 1200 (quite how the men of Ipswich

would have known this is not clear). It seems likely, however, that

in many towns formal councils evolved out of informal counselling or

some quasi-judicial body; I have discussed this

elsewhere and will not go into

the matter again here.

The task of the council was not, at first at least, to stand in

place of the community in assenting to local legislation or other

executive decisions. It was to advise the executives and

to actively participate in the formulation of legislation and decisions.

The urban constitution continued to provide for general assemblies

at which the community could be sounded out on important matters.

But during the latter half of the fourteenth century and continuing

more strongly into the next, we see some significant changes taking

place, with attempts to redefine the political community by

restricting popular participation to the

enfranchised segment and

to major occasions, such as elections; and/or to substitute for

the assembly a second (lower) council intended to represent

the interests of the rank-and-file or, sometimes, the crafts –

which suggests growing recognition that the original (upper) council

had failed to represent popular opinion, as opposed to the interests

of the class from which it was drawn.

The complex reasons for this change are still imperfectly understood,

and I always feel as though venturing into quagmire when I try to

summarize the trends. In an urban population where the gap between

rich and poor had grown, in part as the wage-earning class was swollen

with immigrants, where the wealthier burgesses now had as much if not

more in common with the rural gentry, and where economic success was

more dependent on competition rather than collaboration, it must have

been increasingly difficult to identify a "common good". Socio-economic

differentiation brought with it more class consciousness and corresponding

attitudinal change, a growing divide in trust between the urban estates.

Achieving social harmony was relying more and more on ceremonies that

symbolized at the same time hierarchy and unity, and more attention

was given to proceduralism and orderliness, to ensure that

political meetings were not disrupted by unruly mob behaviour. The

desire for order began to take precedence over the principle of

community consultation. With new magisterial powers delegated by

the king to local government, and with local custom increasingly

superseded by national statute, it became easier for the urban

ruling class to divorce itself from the concept of the community as

the pre-eminent source of authority. Theory notwithstanding, the

practical operation of government was in the hands of an elite, and

the fifteenth century saw a largely successful effort towards capturing

this reality within the urban constitution; the effort included

dispensing with popular assemblies. These trends tended to proceed

more rapidly in the larger towns, where social, economic and

political divides were more marked.

Two other, related, trends in the development of the political system

should be mentioned. One was that the concept of community assent,

as a collective and unanimous agreement to political decisions, was

replaced. The "what touches all..." maxim implied unanimity, and

urban records of decisions often claimed not merely the consent of

the community, but of the entire community. It was not

the role of such records, or in the interest of local government,

to chronicle debates or political manoeuvring that may have lain

behind decisions; nor have we much evidence on whether, at

borough elections in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries,

voting was conducted through careful counting, through loudest shout,

or some other method. As the recognition sank in that a council could,

in some regards at least, substitute for the entire community, it

opened the door for the notion that a section of the council might

substitute for the entire council. The challenge of achieving full

council attendance or of consensus within conciliar ranks made

the concept of majority vote attractive. It was usually a

numerical majority, although some philosophers argued that quality

(i.e. of the councillors, in terms of experience, wisdom, status)

might also be a governing factor – a matter which seems less

arcane in the context of English medieval towns, if one considers

the emergence of an influential elite

within the ranks of the council.

That upper elite is one indication of the second trend that must

be mentioned, which concerns the changing relationship between

executive and council. Maud Sellers [York Memorandum Book,

part II, Surtees Society, vol.120 (1911), v], perhaps influenced

by Norwich's historian William Hudson, distinguished between the

"communal period" of borough government and the "magisterial period".

Despite being prone to the inadequacies of any generalization, this

may be one useful way of thinking about the changing character of

urban government over the course of the Late Middle Ages. By

"magisterial" Sellers had in mind a government focused on the

executive officers (mayor and bailiffs), although Edward Miller

later narrowed this definition to the mayoralty alone [A History

of Yorkshire: The City of York, Oxford: University Press,1961, 70].

But we would do better to think of it as government focused on a

small group of particularly influential townsmen, highly experienced

in government (through having borne the mayoralty), and assigned

special judicial authority.

The case of Beverley, where the council became so prominent that

an executive magistrate was dispensed with entirely, may at first

glance appear to be an exception to the rule. But perhaps we are

missing the point. At Lynn and at York, for example, we see in

the late fourteenth century power being more evenly shared among

a group within urban society, as restrictions were put on the

frequency with which a man might hold the mayoralty; such provisions

may have been intended both to spread the burden and to prevent

the office acting as a vehicle for political dominance. At

Kingston upon Hull in 1379, the subjection of mayor, bailiffs and

chamberlains to the supervision of a council of eight, whose

members could not be re-elected until after an interval of three

years, could be interpreted as a democratic move; but it is just

as likely to be a move by the urban upper class as a whole to bring

local government to rein.

During the thirteenth century the nascent mayoralty relied in part

on a cult of personality; we find individuals who provided strong

leadership being maintained in power for consecutive terms; some

of the earliest mayors seem to have held office for several years

in a row. This was perhaps the result of popular demand, or perhaps

due to the prominence of a controlling interest in the town. At

that period a conciliar group was hazy: even though it is partly

attributable to the poverty of urban archives that we see little

of such a group, it is also likely that such a group was relatively

informal, notwithstanding the evidence

of Ipswich which is known only through the rewriting in the

late thirteenth century, at the instance of a group representing

conciliar interests. The emergence of a conciliar institution

within local government should perhaps be viewed in a similar light

to the development of a baronial interest intent on placing a check

upon monarchical power.

By the close of the fourteenth century we see the mayor as less

of an urban monarch and more as the president of a group of peers.

Only in special circumstances might one acquire unusual prominence

through re-election to consecutive terms – such as William Frost

at York during the late 1390s and early 1400s, when the city had to

come to terms with the major new powers it had acquired, or

William Appleyard at Norwich who was instrumental in obtaining

county status and a mayoralty for the city. The constitutional

role of the council was by now not only formalized but entrenched

and power was devolving towards it. It was possible for leading

townsmen to exercise considerable influence from within the council

without being in occupation of the mayoralty; Nicholas Blackburn

at York and Richard Whittington

at London are examples of men who had served long, performed well

as mayor, and continued to have command respect and exercise influence

in those years when not mayor. These men of experience and authority

were needed as the scope of judicial administration of urban government

necessarily increased, to ensure continued independence from

external authorities in an age when the royal government control

over justice was extending; above all the delegation of

Justice of the Peace authority to that select group of townsmen

provided the bolster that established an elite within an elite.

Yet even as they were obtaining their enhanced independence from

county officialdom and increased authority over the urban community,

they were being tied more directly, more closely to the

central government and to the will of the king. While, socially

and economically, they were building closer ties to the landed gentry

of the county, whose interests were often not the same as those of

the urban traders.

|

|

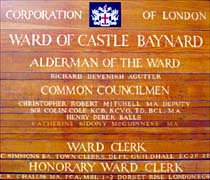

Housing administration in confined spaces, such as guildhalls,

was one of several factors encouraging the development of forms of

government based on delegation of authority from the community to

a limited set of representatives. Representation and restrictiveness

are two sides of the same coin.

(click on the images for enlarged versions and more

information)

|

|

|

Political conflict

In the above discussion we can see some of the causes for

political conflict within medieval towns. Before reviewing that,

it should be noted that many conflicts were occasioned not by disputes

internal to the community, but by those between the community and

other authorities. These might be disputes with the lord of

the borough – particularly where that lord was a conservative

ecclesiastical institution – prompted by the desire for

greater autonomy. Whereas the king, as an absentee landlord, was

less resistant to leasing out new privileges, extensions of jurisdiction,

or sources of income, lords with a local presence were more inclined

to hold onto their jurisdiction and try to milk it for whatever revenues

it could bring in. Or again the disputes might arise from a

competition for jurisdiction, territorial or commercial, with a

manor, market, or another town in the vicinity.

Such disputes sometimes served to instil

a sense of solidarity within the community, but on other occasions

might divide local opinion and even prompt internal power-struggles,

often with an alliance of convenience between the lord and the

lower class, in opposition to the ruling class.

External opponents were useful tools for giving an urban populace

a sense of united purpose. But such enmities could not be perpetually

pursued. There was ample time for townspeople to look within and

realize that some of their principles – community, the common good,

justice for all, social harmony – were not well reflected in

the practice of government. The community was a collective of

individuals, motivated at least in part by self-interest, and a

collective of other groups, each of which had its own interests.

Mutual support for the purpose of common prosperity must have been

a more attractive proposition for those in the lower ranks of

urban society, than for those who had risen to the top. Wealthy townsmen

could attribute their success as much to their personal capabilities

and individual initiative, not forgetting family connections, as

to membership in a privileged community; many may also have felt

that their superior characteristics and skills entitled them

to a dominant role in government.

The task of governing was not an easy one. Urban rulers were torn

between loyalties: to the community, to family, to their trade, to

their social peers, and to their personal business. The difficult

choices faced in reconciling those interests, and the corresponding

demands on their time and energy, only increased as the

Late Middle Ages progressed. The drawn-out foreign wars in which

English kings engaged during the late thirteenth and fourteenth centuries,

along with their heavy demands for financing through taxes and

their adverse and sometimes disastrous effects on commerce, put

a pressure often severe on urban resources. The growth of the

English cloth industry added another complication by encouraging

ambition among the cloth-producing and cloth-retailing groups, who

wanted a share of the decision-making power in the hands of established

merchants who had built their success on trade in agricultural produce

and other raw materials. In fact, there was periodic if not

continuous pressure on established urban families to maintain

their socio-economic position as capable new men migrated to

the town or rose from the lower ranks. In some towns, such as

Colchester, the ruling class was not so heavily mercantile that it

had difficulty incorporating the nouveaux riche. But where

the mercantile elite had been long entrenched, as at London,

tensions inevitably resulted as different interest groups quested

for a share of power. The ramifications of national political conflicts,

bad harvests and their effect on the urban food supply, the

demand for higher wages after plague had decimated the labour-force,

the growing complexity of the national legal system, the scare

given to the establishment by the Peasants' Revolt, are other

factors impacting on the challenges faced by local administration.

It was too much to expect that local administrators could maintain

a harmonious balance of interests – politics is more pendulum

than a balance. It was easy to succumb to the temptation to favour

one's own, although we should not automatically assume that many

did. The common good, virtuous government and social harmony were

ideals; the failure to achieve them was more conspicuous in some

cases than in others. We find complaints about, and popular outbursts

against, maladministration from the second half of the thirteenth century

into the first half of the fifteenth, and so far no clear pattern

has emerged to explain the timing – perhaps there is no pattern.

The problem was not blamed on unattainable ideals or flaws in

the political system per se, but on human failure: greed

and corruption on the part of specific rulers. Embezzlement of

communal funds, unjust assessment of taxation, perversion of justice

were the types of charges commonly levelled, and they speak to

the values we have already noted. The failure was seen as human,

not systemic, and the usual solution was typically to replace

the erring rulers with others from the same class and introduce

greater fiscal accountability and limits on the behaviour of officials.

In fact, it might have been difficult to significantly alter

the political system in a way that would have been acceptable to

the king. In the latter phase of internal political conflict, in

the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, concerns were

less over misgovernment than constitutional changes that were

putting urban rulers beyond the control of the populace.

Indirect election of councils or executives and the transformation

of councils into life membership bodies, gaps in whose ranks were

filled by co-optation, fractured the chain of authority and reduced

the prospects for men of ambition to rise to the highest levels

of society.

Historians have much debated the character of internal

political conflicts within English towns. If there is no consensus,

it is partly because our knowledge of the conflicts is in most

cases sketchy, particularly as regards motivation of the players.

It is partly because we cannot always take at face value the statements

of official records. And it is partly because the causes were complex,

varied from case to case, and were probably not well understood even

by those involved. What appears to be a popular movement seeking

political reform was often a mix of interests, some or many of

which were likely self-seeking. There was certainly a political

dimension to the conflicts, even if the notion of a struggle

between democracy and oligarchy owes more to the perspective of

nineteenth-century scholars, their eyes on municipal reform of

their own era, than to any conscious or overt ideological differences

of the participants. There were no political parties in the

modern sense; to avoid misleading modern audiences, historians

prefer to talk of political alliances by using the term "faction",

in part because they usually surface in the context of factionalism,

i.e. conflict.

We can perceive a variety of dimensions to factions. From one

perspective we can identify personal ambition for power, whether

on the part of one or more outsiders or disaffected insiders, or

family rivalries at play in a political arena. From another we

might see a clash between rich and poor, the powerful and

the disempowered, but such outbursts were generally reactive,

without any clear agenda, unless there was some kind of strong

leadership; it may have been the appearance of such a leader

that explains the timing of political unrest. From a third, a

power-struggle between different economic interests, such as

craft vs. mercantile; but socio-economic inequalities, as we

have noted, were less an infringement of medieval values than

were abuses of positions of trust. Nor can we ignore the possibility

of national events having a ripple effect on local affairs.

More in-depth study of more episodes of political division will

be needed before we can see if any general conclusions may be

drawn about the phenomenon.

We focus on urban conflicts because they are the more conspicuous

events in a history largely unwritten, and of course because they

are fascinating. But it should not be thought they are typical,

nor that the picture of urban society we see through them is

necessarily normal. They were not really revolutionary, in that

they were not trying to overthrow the existing order. Furthermore,

there was some recognition, beginning with Magna Carta, that if

a ruler acted outside the law or failed to uphold the law, or

promulgated law for personal gain of the advantage of an interest

group that ran counter to the common good, such rule was unjust.

In this situation, it was believed that aggrieved parties should,

in sequence, speak seek out against injustice, seek redress through

the legal process, and try to persuade the ruler to reform; if

that failed, then the final and justifiable resort was to use

armed force to protect communal rights and depose the offending ruler.

In the case of towns, theoreticians argued that the extreme measure

was only acceptable if supported by the entire community. Hence,

in urban conflicts we often seem to find complaints to the king,

followed by attempts to introduce political reforms (either by

winning control of the administration, or through pressure-tactics

of popular demonstrations), before the most serious outbursts of

violence take place, with the name of the community invoked at each

stage.

Let me reiterate that such outbursts are exceptions to the rule,

although when political passions were aroused the resulting disputes

could be bitter and sometimes prolonged. Allowing for the biases

of surviving records, we are safer to assume that acquiescence

in governmental decisions was a more typical behaviour

of the community, for politics was about lordship and loyalty.

Yet a recognition that rulers relied on such acquiescence is reflected

in the resort to mob action to express popular displeasure. However,

ultimately, political conflict resolved to the advantage of the

ruling class, even where they had to make power-sharing compromises,

as the monarchy was inclined to support the status quo and to

reinforce it so that it could better meet its own priority of

maintaining social and political order.

|

|

In the seventeenth century the London mob became notorious for its

rioting; the disempowerment of the lower classes had left no other

avenue for expression of discontent or resistance to tyranny. Mob action

was equally a concern for, if not a fear of, London authorities from

thirteenth to fifteenth centuries.

|

The character of government

Historians have played rather loose and free in labelling

urban governments in medieval England as oligarchic; they have

become ensnared by an historiographical tradition. The control

of government by the upper class, with the acquiescence of lesser

social orders, does not make it oligarchic; the term would more

usefully be restricted to its Aristotelian meaning of monopoly of

power for selfish gain or other corrupt purposes. When urban governments

became oligarchic, as sometimes happened, we can see that it

was considered unnacceptable from the popular complaints and

open opposition, these often accomplishing at least a partial

corrective to the situation. Aristotle would likely have classed

the government of medieval English towns as aristocratic, which for

him did not have the negative connotations it has today. Today,

democratic is probably the closest term we have to categorize it,

for it is hard to see substantive differences between government

in medieval towns and modern western democracies.

It is easy to fall into the trap of focusing on periods of

popular discontent in towns and assuming that medieval townspeople

were constantly disillusioned with government. To put things into

a comparative perspective, let me describe modern public perspectives

on the character of government in my own country, Canada. A

survey-based study (sample size 1500) conducted by Leger Marketing

in April 2002 concluded that the majority of Canadians believe

Canada's political system to be corrupt at every level of government.

This is, it should be remembered, in a nation considered one of

the more open democracies of the world. Of those surveyed, 69%

believed that there was a high or moderate level of corruption at

the federal level, 68% felt the same about the provincial level,

and 53% of the municipal level of government. Politicians themselves

were the most highly blamed for this perceived state of affairs,

while their entourage and senior civil servants were the groups

next targeted for blame. One particular area of grievance was

the channelling of public money into the pockets of politicians'

peers (i.e. other members of the same capitalist class), via

purchases of goods and services. Furthermore 22% of Canadians felt

that their political system is not truly democratic. Although

the Prime Minister responded to the survey with a prompt denial of

corruption in government, within the next few weeks several Cabinet

ministers would lose their posts through scandals.

A second survey (sample size 2000) touching on the health of democracy,

conducted by the Association for Canadian Studies and Environics/Focus

Canada in June/July 2002, found that three-quarters of Canadians

believe the wealthy members of society have too much influence

over political decision-making, while over two-thirds feel

the same about a superior external power (the United States)

and about leading commercial interests. Individuals and small

businesses are perceived as being correspondingly deprived of

political influence; individuals in particular are seen as

disempowered. I, for example, could not imagine successfully

pursuing political power at almost any level of government, lacking

the connections and the financial resources required. Only a

very small minority of citizens seek active participation in

government, and the extent of consultation (however superficial)

of the citizenry on government decisions is far more restricted

than it was in medieval towns – most calls for referendums on

matters of import are rejected.

We should bear in mind that public criticisms of the political system

are not necessarily valid. What is important is that they represent

public perceptions and suggest a disenchantment, warranted or not,

with the power-structure and with politics. Yet it is a system of rule

in which, for the most part, citizens willingly acquiesce, criticism

peaking only when governmental acts are widely perceived not to

be benevolent or for the public good. The same cynicism, or realism,

depending on one's standpoint, is seen in the statement of a

newspaper editor that: "clearly those attracted to executive power

today seek it via the legislature, posing as the people's tribunes

at election time so as to become their masters." [John Robson,

"Gay marriage vs. Magna Carta", Ottawa Citizen, 17 July 2002,

p.A16] Many people living in western democracies hold the opinion

that politics by its very nature fosters corruption, whether

manifested through rhetorical dishonesty or through misuse of power

for personal benefit, and they feel excluded from the decision-making

process. A sense that such public consultation as exists is largely

for the sake of show and that one individual's vote makes little

difference to the outcome of an election have played a role in

de-motivating citizen involvement in the political system,

except through organized interest groups. A fatalist attitude

towards political corruption is visible at all levels: Canada's

Prime Minister, upon dismissing one of his ministers for giving

a contract to a former lover, was quoted in the media as shrugging

things off: "These things happen." It is worth noting that much

of the attention focused, at this time of writing, on

Canada's political system comes towards the end of an administration

which has held several consecutive terms in office, and one of

the complaints is that too much power has become focused in

the office of the Prime Minister.

Dangerous though comparisons can be, there are nonetheless many

parallels here that might be drawn with the situation in English towns

in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, when our

records of local government have become fuller and more regular.

A similar growth in alienation from the political system, a feeling

of exclusion from meaningful participation, a fear that power-holders

act to protect their own interests more than the interests of

the community – interests that, as noted, had become increasingly

complex and difficult to reconcile – and an increased attention

to supposed corruption or maladministration, are features that become

more pronounced in that period, although we cannot be certain how

much this is a facet of the better records. Popular frustration may

help explain why there was a preparedness to look for leadership

to men on the peripheries of the ruling elite, men held back on the normal

path of political advancement and prepared to seek power by championing

popular reform. Fear of this may similarly be a factor in explaining

why more strenuous efforts were made by the authorities to create

disincentives to popular dissatisfaction, by imposing heavy punishments

on aggrieved members of the community who criticized, slandered,

spread rumours about, or even laid hands on members of the governing body.

Whether resentment of the ruling elite was justified is not easy

to assess. Popular discontent is muddied by the struggles of

different interest groups within the community, mainly

economic interest groups, to increase their influence, by

personal ambitions or vendettas, by divisions within the ruling class,

and by long-standing conflicts between internal and external authorities

for jurisdiction in urban matters. We cannot rule out the possibility

that medieval complaints about urban governments are sometimes, or

in part, the consequence of false perceptions or misunderstandings.

I have elsewhere indicated that

the taxation system used in Lynn was inevitably subject to

misunderstanding. Taxation is inherently unpopular; in my

own time strenuous efforts are being made by governments at all

levels to lower taxes or at least prevent tax increases, at

a devastating cost to social services, so politically unpopular

are taxes. We must therefore be careful in taking medieval complaints

at face value. Which is not to say, either, that complaints

were groundless.

The central government was prepared to intervene where it seemed

that there were grounds for accusations of maladministration or

corruption. The concern was partly for the king's oppressed subjects,

partly over the threat to sources of royal revenues, and partly

because the king considered that all exercise of power was by

royal delegation, which gave him an inherent interest in local government.

It was in part the royal interventions that tended to be frequent

in the thirteenth century – often resulting in suspension of

city privileges, including self-government, and imposition of more

direct royal rule – that encouraged the urban ruling class to

document the urban constitution.

Populist sentiment and values in urban society were ultimately

stifled by the monarchy, whose interest – like that of

townspeople – was less in the character than in the effectiveness

of government in achieving the common good. From the perspective

of the king, however, the common good involved the standardization

of administration across the realm and the preservation of law and order.

It was partly in consequence that, at the close of the Middle Ages,

borough government had become more closed, with the citizenry

less directly involved in matters such as elections and the scope

of elections having been narrowed (when alderman were chosen

for life, and the mayor selected from their number), albeit

that the number of citizens involved in the corporation had

expanded with the introduction of large second councils.

However, the additional judicial powers accorded to an

elite-within-the-elite by the central government made it easier for

a small group with little accountability to the populace to dominate

the larger towns.

The emergence of relatively independent local government, with

a developed corporate identity and more elaborately structured

administrative hierarchy, characterized in part by greater

bureaucratization and proceduralization, took place in the context

of a growth in scope and strength of the central government of king